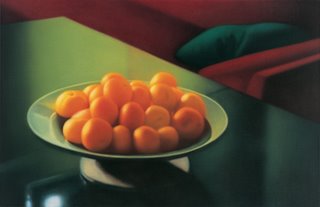

Matvey Levenstein, Clementines, 2000.

COURTESY LARISSA GOLDSTON GALLERY, NEW YORK

The controversy around painting from photographs continues as new generations and new image-making technologies keep the debate alive

By Linda Yablonsky @ ARTnews

The image that the Whitney Museum has chosen to promote “Day for Night,” its 2006 Biennial, is an extremely close view of a woman’s eye. The eye is green and heavily made up with hot pink shadow and sequins. Taken from a 5-by-9-foot painting by Marilyn Minter, it has a tawdry sort of glamour.

The eye appears in color on the dust jacket of the exhibition catalogue, while an enlarged detail is printed in black and white on the cover. The original, Pink Eye (2005), was partly fingerpainted in enamel on aluminum. In reproduction, however, it looks just like a photograph.

In fact, Minter created the painting from two different photographs that she shot herself and combined on a computer in Photoshop, the digital equivalent of a darkroom, before projecting the result onto her painting’s surface and tracing it. That is enough to make some people scream—despite the power of the image, the evidence of the artist’s hand, and her transformation of the source.

These days, photo-based painting is as common as rain and just as inevitable, as younger artists such as Nick Mauss, Lucy McKenzie, and Wilhelm Sasnal take up the practice and exploit it. Yet it often complicates the public’s understanding of art and can easily put painters who use photographic aids, including computers and projectors, on the defensive. The question is: why? Why should a painting based on a photograph be considered a less legitimate work of art than one painted from observation or one that is simply abstract?

READ ON

No comments:

Post a Comment